As I’ve traveled the country these past 4+ years launching R1 I’ve learned a lot, with the help from so many others, about the behavioral health industry, workforce shortages, and the basic competencies required for practitioners to be effective at all levels of practice. From masters level clinicians to newly graduated counselors, psychology technicians, or certified peer support providers, we’ve had an opportunity to work with them all. Although everyone seems to know what the Stages of Change are and some of the basics about them, there are still a vast majority who can not put the Discovery Cards behaviors into the correct stage piles, ask an effective motivational interviewing question related to the behavior displayed, or have even heard about the underlying Processes of Change. Learning the fundamentals for the core behavioral health topics is our mission. Applying them successfully in practice is our ultimate goal. Few get into the big game and hit the winning shot unless they’ve first spent countless hours in practice. Practice is where players participate in station drills learning and repetitiously running through the basic skills over and over and over again (dribbling, passing, blocking out, shooting, etc.) until they becomes part of the muscle memory and can be applied effortlessly when the game starts. This is true too for applying any new skill in any professional discipline. In our earlier post, The 5 Stages of Change and the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) — Do You Know the Basics? we shared the fundamental concepts of the TTM and introduced the Processes of Change via the Stage-Matched Processes table. Today’s post’s purpose is to revisit these basics and share more about the 10 Processes of Change as a way to increase your own or your team’s knowledge, skill and effectiveness. Let go to Stages of Change practice and jump into the Processes of Change station drills. Remember, practice is a safe place for learning, developing new skills, and building confidence to apply them effectively with a variety of populations in different types of settings. For those that have met me speaking at a conference or in one of our R1 training session, your may remember this… “it’s all about practice — practice, practice, practice”.

Stages of Change Defined — A Quick Refresher

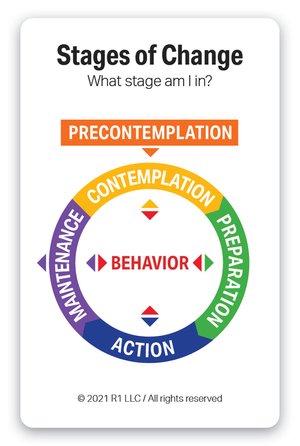

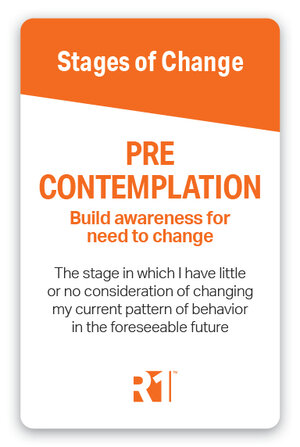

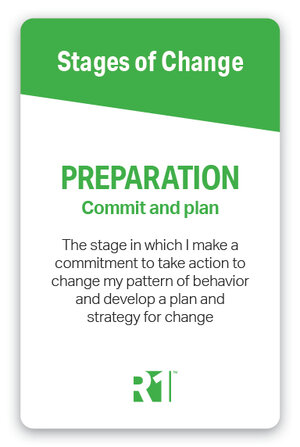

As we shared in our earlier post, and have learned from Drs. James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente, the TTM recognizes change as a process that unfolds over time, involving progress through a series of stages. The TTM highlights the fact that individuals move through a series of five stages — precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance — in the adoption of healthy behaviors or the cessation of unhealthy ones. (Play 2-minute video now) While progression through the stages of change can occur in a linear fashion, a nonlinear progression is common. Individuals often recycle through the stages, regressing to earlier stages and progressing to later ones. Although the time a person stays in each stage is variable and unique to each individual’s situations and circumstances, the tasks required to move to the next stage are consistent. Certain principles and processes of change come into play at each stage to reduce resistance, facilitate progress, and prevent recurrence of the behavior. Only a minority (usually less than 20%) of at-risk individuals are prepared to take action toward change at any given time. As a result, action-oriented guidance can miss serve individuals in the early stages, as they may not be ready to take action. At each Stage of Change, there are specific intervention strategies that are most effective at helping the individual move to the next stage of change and subsequently through the model to the Maintenance Stage, sustaining the desired behavior which is the goal. These intervention strategies are known as the Processes of Change.

The 10 Processes of Change Defined

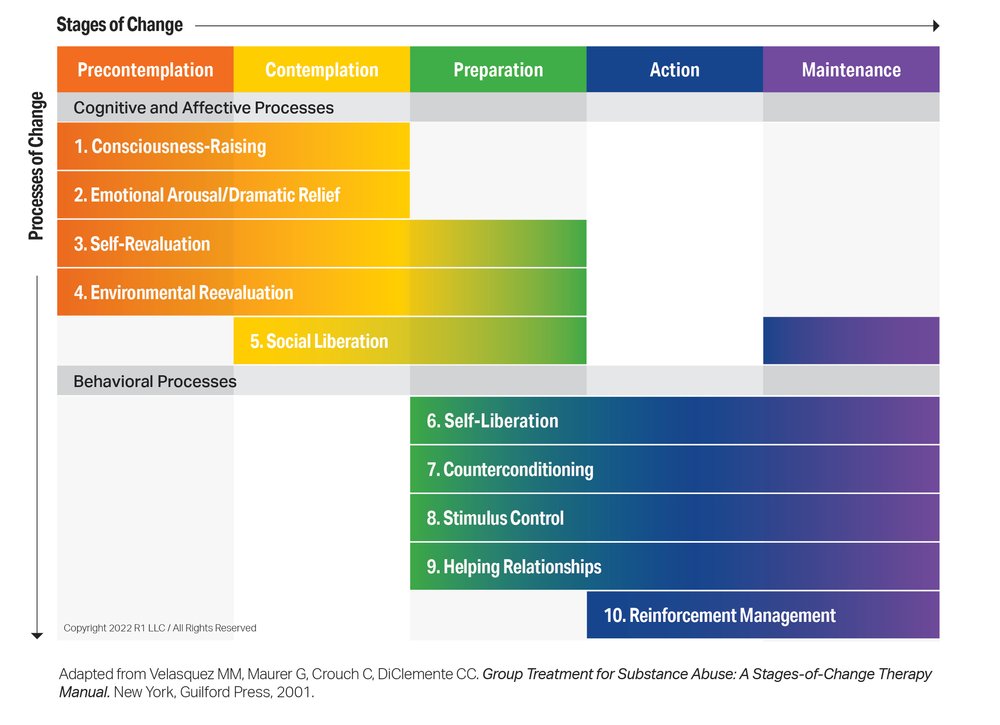

While the Stages of Change are useful in explaining when changes in cognition, emotion, and behavior occur, the Processes of Change help to explain how those changes occur. These ten processes, which are highlighted in the table and defined below, can enable individuals to successfully progress through the Stages of Change when they attempt to modify problem behaviors and attain desired behavior change. The Processes of Change are divided into two groups: 1) cognitive and affective processes and 2) behavioral processes. According to research on the TTM conducted by Drs. Prochaska and DiClemente and their colleagues, interventions to change behavior are more effective if they are “stage-matched” — that is, interventional

techniques related to the specific processes are matched to the Stage of Change that individual is in. The table below

shows the Processes of Change matched to the Stages of Change, with color bars indicating the processes employed as

individuals move through stages.

R1 Challenge: As you review the table below and the details about each of the 10 Processes of Change, challenge yourself to identify 2-3 motivational interviewing questions that you will ask individuals when you determine which Stage of Change they are in and which Processes of Change will be most helpful.

PROCESSES MATCHED TO STAGES - THE PROCESSES OF CHANGE EMPLOYED BY INDIVIDUALS TO MOVE THROUGH THE STAGES OF CHANGE

COGNITIVE AND AFFECTIVE PROCESSES

- Consciousness-Raising — build awareness: This process is characterized by individuals seeking to increase their awareness through information, education, and feedback about their current pattern of behavior, and/or their potential new behavior. This comes in the form of self-observation, interpretations, evaluations, conversations about observed behavior, and even confrontations,with other. These conversations can be centered on the impact, cost, loss, or harm resulting from the problem behavior or the benefits / vision of the benefits arising from the potential new behavior.

- Emotional Arousal / Dramatic Relief — pay attention to emotions and feelings: Individuals feel fear, anxiety, shame, pain, or guilt because of their unhealthy behavior, or feel inspiration and hope when they learn about how people are able to change to new healthy patterns of behavior. This process is characterized by one experiencing and expressing emotions and feelings about the problem behavior, grieving losses, and role playing as a tool to produce insight. In this process, helping individuals express emotions such as anger, fear, pain, guilt, shame, joy, strength, and love becomes a vehicle for change.

- Self-Reevaluation — create a new positive self-image: Individuals realize that the new healthy pattern of behavior is an important part of who they are and aspire to be. The focus of this process is to foster the emotional and cognitive reappraisal or clarification of values (one’s purpose, meaning, direction, or alignment with environmental standards) with respect to the problem behavior and life circumstances resulting from it. Values are at the core of change theory, are deeply rooted in belief systems, and when activated are infused with emotions and feelings.

- Environmental Reevaluation — notice impact on others: Individuals realize how their unhealthy pattern of behavior negatively affects others and how they can have more positive effects by changing their behavior. This process is characterized by individuals assessing and considering how the problem behavior affects their physical and social environment, taking stock of the impact, cost, loss, or harm to others, and empathy training.

- Social Liberation — notice public support and gain alternatives: Individuals realize that society is more supportive of their new healthier behavior. In this process, individuals increase awareness and acceptance that alternative, problem-free, healthy lifestyles in society exist and are available to them.BEHAVIORAL PROCESSES

- Self-Liberation — make choices and commitments: Individuals believe in their ability to change and make choices, commitments, and re-commitments to act on their belief and stay the course for their changed behavior. This process is practiced in new decision making strategies, commitment enhancing techniques, resolutions, and exploration to find purpose and meaning in life.

- Counterconditioning — use substitutes: Individuals substitute new healthy ways of thinking and acting for unhealthy patterns and behavior. This process is characterized by one’s ability to substitute alternative behavior for the problem behavior using healthy emotional regulation practices or coping strategies such as acceptance, mindfulness, connection with others, physical exercise, spirituality, and positive self-affirmations.

- Stimulus Control — observe and manage environment: Individuals use reminders and cues that encourage healthy behavior as substitutes for those that encourage unhealthy patterns of behavior. In this process, individuals learn to how to observe and evaluate their environment and identify causes which trigger or activate their emotions and move them toward the problem behavior. Learning how to add new stimuli that encourages alternative behavior, restructuring the environment, and avoiding high risks cues or situations is the focus of this process.

- Helping Relationships — get help and support: Individuals find people who support their new healthy behavior. This process is characterized by individuals accepting, trusting, and utilizing the support of caring others during attempts to change the problem behavior. Seeking and accepting help from a broad range of social groups and professionals is the focus of this process — healthy family, friends, social support groups, individual counseling, physical and mental health professionals, peer support providers, etc.

- Reinforcement Management — use rewards: Individuals increase the rewards that come from positive healthy behavior and decrease those that come from negative unhealthy behavior. This process is characterized by rewarding oneself or accepting rewards from others for making changes in one’s behavior, building contingency contracts, and overtly or covertly reinforcing ones behavior through self-rewards. Celebrating progress in healthy and safe ways is at the core of this process.

Copyright 2021 R1 LLC / All Rights Reserved. Use of this article for any purpose is prohibited without permission.

Questions to Explore

Answer these questions for yourself or with your team.

- Do you find the Processes Mapped to Stages Model helpful in thinking about your experience counseling / coaching clients with mental health conditions or substance use?

- Do the Process of Change make sense to you? Are the categories helpful and easy to understand?

- As you look back over relevant counseling / coaching experiences, do you see how individuals move through the stages via the processes?

- How does understanding the Processes of Change help you engage with clients more effectively?

- Do you see how individuals get stuck in certain stages? What keeps them stuck? How can you help them keep progressing through the stages by addressing the Processes of Change?

- How can you incorporate Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques to help individuals move through the Process of Change and therefore progressing through the Stages of Change?

- How can you incorporate these ideas into your next client one-on-one or group session or clinical supervision session with your team?

Facilitate Engaging Group Activities

Stages of Change Discovery Cards and Group Kits – Engagement Tools

Integrating these tools into your groups will allow individuals to build their own vocabulary, think about these concepts concretely, and put their choices into action. Visit the R1 Store to learn more about these evidence-based behavioral topics and models. The cards are an amazing tool for exploring these topics with individuals or groups.

References

Bandura A. “Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency.” American Psychologist 37:122–147, 1982.

Bandura A. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84:191–215, 1977.

DiClemente CC. Addiction and Change. New York, Guilford Press, 2018.

Janis IL, Mann L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment. New York, Free Press, 1977.

Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM. Changing to Thrive. Center City, MN, Hazelden Publishing, 2016.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. “In Search of How People Change: Applications to the Addictive Behaviors.” American Psychologist 47:1102–1114, 1992.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. “Stages and Processes of Self Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51:390–395, 1983.

Velasquez MM, Maurer G, Crouch C, DiClemente CC. Group Treatment for Substance Abuse: A Stages-of-Change Therapy Manual. New York, Guilford Press, 2001.

University of Rhode Island website 2021, Transtheoretical Model, Processes of Change

Here are a few ideas to help you learn more about R1 and engage others on this topic:

- Share this blog post with others. (Thank you!)

- Start a conversation with your team. Bring this information to your next team meeting or share it with your supervisor. Change starts in conversations. Good luck! Let us know how it goes.

- Visit www.R1LEARNING.com to learn more about R1, the Discovery Cards, and how we’re creating engaging learning experiences through self-discovery.